SUPPORT VOX!

❤️ ☺️

SUPPORT VOX! ❤️ ☺️

The Zournal of Repeated Things

OLUWAFEMI

Friday, May 2, 2025 – Sunday, June 15, 2025

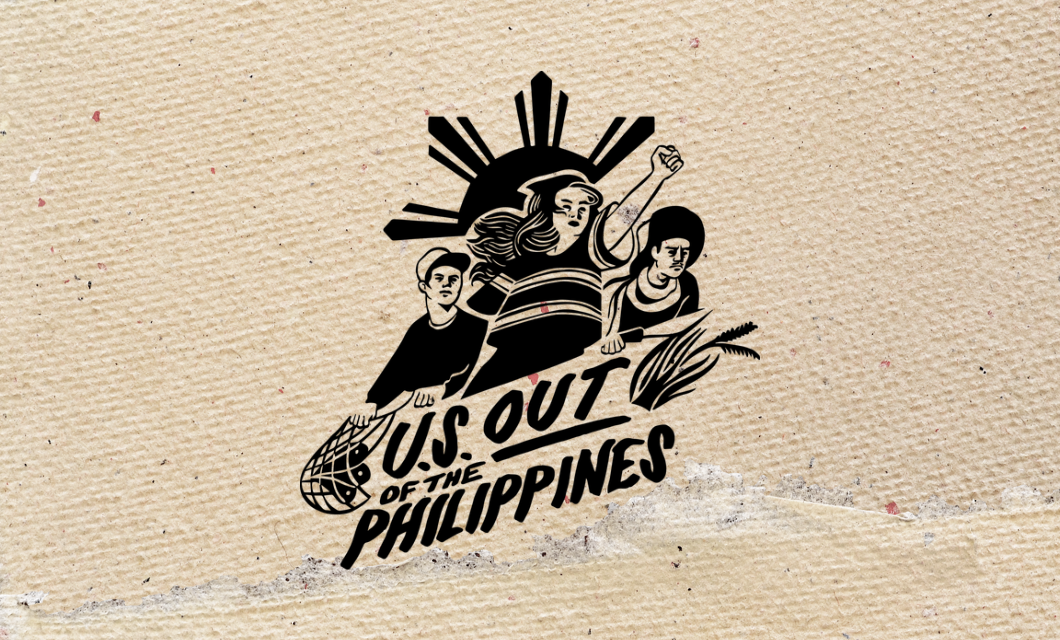

No Saviors, We Free Ourselves

Presented by Anakbayan Philadelphia

Friday, May 2, 2025 – Sunday, June 15, 2025

Nightlarking

Julia Gould & He-myong Woo

Curated by Cynthia Zhou

hearth

A painting show of works by Evan / Eve Greensweig

🎥🦈 OPEN CALL: SHARK TANK WEEK 🦈🎥

Presented by Long Shot

🦈 Submissions due June 1st

Support Vox! Join us for our Summer Fundraiser!

Current & Upcoming Exhibitions

Friday, May 2nd – Sunday, June 15, 2025

Friday, May 2nd – Sunday, June 15, 2025

Friday, May 2nd – Sunday, June 15, 2025

Friday, May 2nd – Sunday, June 15, 2025

Upcoming Events

Vox News & Updates

🎥🦈 OPEN CALL: SHARK TANK WEEK 🦈🎥

Presented by Long Shot

Screening: Thursday, June 26, 2025 (Fourth Thursday!)

Most likely outdoors at the Philly Rail Park

For Vox Populi’s 20th Annual Juried Show, “First, then, next, finally,” we are looking for artwork that uses sequencing!

Vox Populi Announces Partners for Black Box Presents Program

We are thrilled to share the full lineup of partners for 2025

Fund art in Philadelphia!

Learn more about how you can support our artist-run gallery ⟶

![Black Box Presents: All Mutable -spasm [embodied resistance]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/643ff7346d0a872ee9f81b9c/1743728709497-QOO60TXPIZE0IA4UKJ62/BlackBoxPresents-WebBanner+%284%29+%281%29.png)